Lima, Peru – Peruvian President Dina Boluarte enacted on August 13 a controversial law which grants amnesty to police, military personnel, and members of self-defense committees accused or convicted of crimes committed during the country’s internal armed conflict (1980–2000). The law also orders the release of convicted individuals over the age of 70.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk immediately condemned the move: “I am appalled by the enactment of this amnesty law, which is an affront to the thousands of victims who deserve truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-repetition, not impunity,” he said.

Türk stressed that international law prohibits amnesty for serious human rights violations.

According to the Geneva Conventions- also known at the Humanitarian Law of Armed Conflicts- authorities in power at the end of hostilities should grant the “broadest possible amnesty” individuals involved in armed conflict, although the International Committee of the Red Cross excludes “persons suspected of, accused of, or sentenced for war crimes” from the possibility of amnesty.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) had also warned in June that such measures are inadmissible.

“Peru must refrain from approving amnesties for grave human rights violations and ensure victims’ access to justice,” the body said, recalling that in the Barrios Altos case —where a covert military unit killed 15 people during a neighborhood gathering in 1991— the Inter-American Court ruled that any laws seeking to shield extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances, or torture from prosecution are “null and void.”

“Canceling judicial proceedings sends a message of indifference toward victims’ suffering. This law will allow the release of those responsible for massacres such as Putis in 1984, where 123 people, including children, were killed,” the NGO warned.

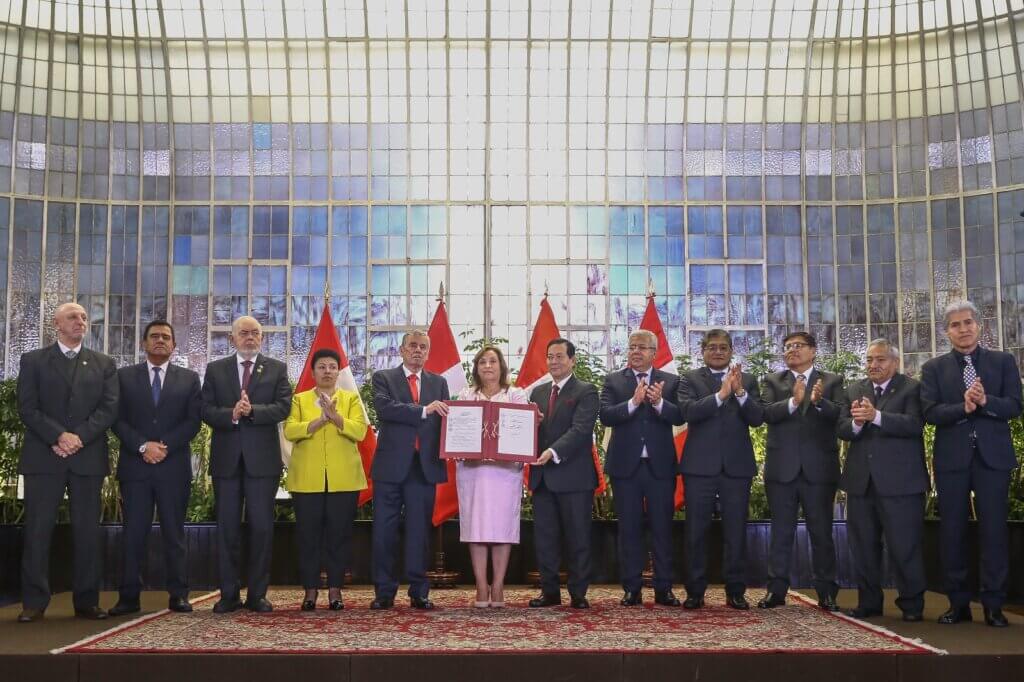

Dina Boluarte signing the Amnesty Law for members of the Armed Forces, the Police, and the self-defense committees who participated in the fight against terrorism. Image courtesy of the Peruvian Presidency.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) was more forthright: “This law is, simply, a betrayal of victims. It undermines decades of efforts to ensure accountability and further weakens the rule of law in Peru,” said Juanita Goebertus, Americas director at HRW.

The organization also noted that the Inter-American Court had ordered the government not to enforce the amnesty while reviewing its compatibility with international law—a ruling that was ignored.

What does amnesty entail?

The newly enacted law halts ongoing trials and voids sentences against security force members accused of crimes committed during counterinsurgency operations between 1980 and 2000.

The National Human Rights Coordinator estimates it could affect at least 156 concluded cases and over 600 pending prosecutions, including those involving extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances, sexual violence, and torture.

Regardless, the Peruvian Congress spearheaded the measure, with lawmaker Jorge Montoya introducing the proposal and securing support from conservative factions. It cleared the Constitution Committee, then chaired by Fernando Rospigliosi, who defended it as a way to end what he deemed “decades of judicial persecution” against police and military officers.

Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) estimates that the conflict claimed around 70,000 lives. While most victims were attributed to the Shining Path and MRTA insurgencies, roughly 30% were the result of the abuses committed by state forces.

The government’s stance

President Boluarte defended the law as a tribute to Peru’s security forces. At the signing ceremony, she said: “We cannot allow history to be distorted, where perpetrators pose as victims and the true defenders of the nation are portrayed as enemies of the homeland.”

Her administration argues that many police and soldiers have faced “unjust and endless” trials, and that the law is a humanitarian step in favor of those who fought terrorism.

For international bodies, the law represents a major setback in the fight against impunity; the UN, IACHR, Amnesty International, and HRW all agree it violates Peru’s international obligations.

Peru’s Attorney General Delia Espinoza also criticized the measure, calling it “an insult to the victims” and “a slap in the face to the international conventions signed by Peru.”

Meanwhile, victims’ associations have announced protests in Lima and other regions. For them, the law is not an act of reconciliation but a blank check for impunity that reopens wounds yet to be healed.