According to international assessments, the low national budget, the meager management of deficient public schools compounded with poor infrastructure and unmotivated teachers are some of the leading causes of a malfunctioning education system in Peru.

Since the beginning of the new millennium, Peru’s economy has been growing. Income per person has tripled and the tourism industry is continuingly blooming. But at the same time education is failing to keep up with these positive trends.

In 2012 Peru came last among the 65 countries that took part in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), that tested the educational skills of 15-year-olds worldwide. In 2015, another assessment was run and this time Peru performed slightly better: it came out 63rd out of 69 nations. But it remains a serious problem for Peruvian students, as only the students of Dominican Republic performed worse in Latin America.

“There are good schools, with great infrastructures and devoted teachers using some appealing methodology and willing to discover student’s talents”, says Mario Diaz, director of the Cusco based NGO Helping Hands Cusco. “The only problem is they’re not accessible for most of the Peruvians”.

Mario has experienced the good and the bad within the educational system. He was born and raised in an underprivileged family. He saw his hard-working father obtain his law-degree after studying for more than a decade in the kitchen at night. The economic change this effort brought to his own family taught him the importance of education. “It’s probably the only sustainable way to overcome the vicious tentacles of generation-long poverty”.

Mario has experienced the good and the bad within the educational system. He was born and raised in an underprivileged family. He saw his hard-working father obtain his law-degree after studying for more than a decade in the kitchen at night. The economic change this effort brought to his own family taught him the importance of education. “It’s probably the only sustainable way to overcome the vicious tentacles of generation-long poverty”.

A good student himself, Mario eventually became a teacher. Over the years, he worked in public schools as well in private ones.

In principle, education is obligatory until 16 in Peru. It’s organized through paid private and free public schools. Afterwards, people can continue studying in universities or technical institutions but it’s often expensive as good education is mostly found in private institutions. Unless you are lucky enough to pass the difficult admission exams and obtain one of the few available, and highly desired, positions at a free public university that has some standing.

Only 3 out of 10 youngsters make it on to higher education. The least likely are children from underprivileged families, living in rural areas and studying in public schools.

Aside from political quarrelling, the establishment of decent education in Peru is hampered by a lot of reasons. There’s the difference between urban and rural life. Often hindered by its geography, there are communities that need 3 hours to reach the school. Some children even walk 8 hours a day. Narrowing distances with technology could lend a hand but with only 11% of the people on the countryside using internet, it’s still a distant dream.

The gap between rich and poor, however, stands out. This difference is reflected in the attendance in public or private schools. According to Mario, Peruvian public schools have a bad reputation.

“Though here in Cusco, there’s one that’s more or less competent”, he says laconically. “My children studied there”

“There are public schools in Lima that have to close doors because of a lack of students. Their parents prefer to spend more on a private school in exchange for a better education. Some private colleges in Lima have soccer fields, swimming pools, theatres. Teachers have a good salary and are motivated to discover the pupil’s talents. I’ve heard of wealthy parents willing to pay up to two to three thousand pesos a month for superior education”.

However, in more rural areas and the surrounding Cusco region, public schools experience an overload that leads to a big loss of quality. And there’s a lack of a follow-up from the national ministry. The demand outweighs the supply. Classes filled with up to 45 children are a common sight. The schools have 3 shifts a day and schoolyards are stuffed with up to 1,000 pupils. This leads to unmotivated teachers, some hanging on, others giving up, but all more concerned about the reproduction of knowledge than offering a more demanding, more pedagogical schooling. However painful, it is also somehow justifiable. Their low wages, overpopulated classes and lack of follow-up compose a logical recipe for deficiency and conformism. Or as Mario says: “Teachers bear a passive, understandable, culpability”.

“Six years ago, the Ministry of Education decided to make one textbook obligatory for all public schools in Peru. Private schools are allowed more wiggling room: the ministry expects them to fulfil only 30% of the book. That was one of the better decisions they’ve made so far. Before that, teachers could fill in the matriculum however they wished. This led to a highly unequal education, whereby quality totally depended on the improvisation and skills of teachers.”

“The book” indeed provided standard quality. But there was the other side of the coin: teachers read the book, and stuck with the book.

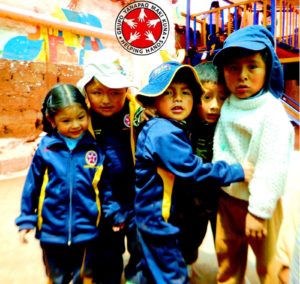

Working as a teacher, the frustrating shortfalls and the substandard level of schooling made Mario decide to take up arms himself. In 2005, together with his wife Rosa, he started Helping Hands Cusco. They first only helped pupils after school with their homework. In 2008, they started their own school, San Gabriel, in a remote area of the modest neighbourhood of Patron San Sebastian.

Working as a teacher, the frustrating shortfalls and the substandard level of schooling made Mario decide to take up arms himself. In 2005, together with his wife Rosa, he started Helping Hands Cusco. They first only helped pupils after school with their homework. In 2008, they started their own school, San Gabriel, in a remote area of the modest neighbourhood of Patron San Sebastian.

“Starting the school was my way of resistance towards the failing education system,” Mario says.

“Recently, rather by incident, I found out that my 9-year-old son has a big talent for playing the violin. As he adores the instrument, we inscribed him in music classes. It made me happy but also a bit frustrated. Why didn’t we discover this talent much earlier? And why didn’t his school assist us in this?

Aiming to offer high-quality education accessible for all social classes, San Gabriel is privately organised, without public support. So far, they have 4 classes and 5 teachers. Their goal is to expand by 2019 and start a secondary school.

They’re able to make ends meet thanks to (mostly international) donations, volunteers and tourist visits. But they rely on monthly contributions of parents as well. To prevent underprivileged families fleeing away to public schools, these are far below the normal ranges and adapted to the individual economic situation. “It’s a necessary evil, but it keeps the parents committed as well”, says Mario.

In San Gabriel, Mario and his teachers want to think outside the box. They work with creative corners, invest in music classes, organize excursions and sports events. And parents are closely connected to the school. His trip to Europe 4 years ago was an eye-opener. “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed is king. As long as you don’t see other possibilities, you’re less likely to change”.

In San Gabriel, Mario and his teachers want to think outside the box. They work with creative corners, invest in music classes, organize excursions and sports events. And parents are closely connected to the school. His trip to Europe 4 years ago was an eye-opener. “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed is king. As long as you don’t see other possibilities, you’re less likely to change”.

In the last months, following a month-long national strike and protests, public teachers finally saw their salary raise up to 2,000 soles.

Mario is proud: “All over the country, teachers leave their jobs in small private schools for a better-earning job in public schools, but ours, earning 500 soles less, are staying”. It characterizes the commitment teachers have towards the educational project. They pull together and believe in the social impact of their cause. In secondary school, especially in rural areas, only 63.7% of the girls between 12 and 16 go to school and only 35 % of them finish secondary school. There is more chauvinism and traditional ideals in rural areas, parents prefer to keep their daughters at home to help in the household.

“I know a woman selling Anticucho (popular and inexpensive street food that originated in the Andes during the pre-Columbian period, ed.) Some years ago she made 20 soles. Now, as Cusco’s economy is doing better, together with her 14-year old son, she’s working harder, making 400 soles a day. But meanwhile her son isn’t attending class, his development is stuck in exchange for money”

Asked what he sees as Peru’s biggest challenge, Mario doesn’t hesitate long. “The infrastructure has to become more relevant. Schools have to generate an atmosphere of creativity and discovery. In a stimulating atmosphere, teachers will feel more motivated, the children and parents will follow”.

Asked what he sees as Peru’s biggest challenge, Mario doesn’t hesitate long. “The infrastructure has to become more relevant. Schools have to generate an atmosphere of creativity and discovery. In a stimulating atmosphere, teachers will feel more motivated, the children and parents will follow”.

But so far, there are few investments from the government. According to a report of Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo Peru invests only 3.7 of the Gross Domestic Product to Education. In comparison: Bolivia (6.5%) and Brasil (6.1%) are spending almost double that. President Kuczynski promised that for 2021 he would raise the budget and minister of Education Vexler recently promised a higher quality of education by that time as well.

Mario points fingers at the regional government rather than the national government. “Though it’s relatively small, there is an annual budget available for regional educational improvement but the irony is it isn’t used. In exchange for a nice handout, the regional official sends it back to Lima, stating they can not use it”

“Can you imagine how much Peruvian talent is wasted? Crowded classes in anonymous schools with stressed-out children trying to sit still in front of a bored teacher who’s yelling drilled answers that don’t really enter their brain. He sighs: “It makes me sad to think about this”